Diabetes - type 2 - InDepth

Diabetes - type II - InDepth; Adult-onset diabetes - InDepth; Diabetic - type 2 diabetes - InDepth; Oral hypoglycemic - type 2 diabetes - InDepth; High blood sugar - type 2 diabetes - InDepth; Type 2 diabetes - InDepth; Maturity onset diabetes - InDepth; Noninsulin-dependent diabetes, DM2, Type 2 DM - InDepth

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of type 2 diabetes.

Highlights

DIABETES STATISTICS

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as of 2016, more than 100 million US adults were living with diabetes or prediabetes. More than 29 million American adults and children have diabetes, and about 86 million have prediabetes, a condition that increases the risk for developing diabetes. About 1 in 4 Americans that have diabetes do not know that they have this disease.

Diabetes rates are steadily increasing among both adults and children.

TYPE 2 DIABETES RISK FACTORS

Risk factors for type 2 diabetes and prediabetes include:

- A previous diabetes test showing impaired fasting glucose (IFG) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)

- Age 45 years or older

- Family history of diabetes

- Being overweight (BMI 25 to 30) or obese (BMI>30)

- Inactive lifestyle and lack of regular exercise

- African-American, Hispanic/Latin American, American Indian and Alaska Native, Asian-American, or Pacific Islander ethnicity

- High blood pressure (140/90 mm Hg or higher)

- Low HDL (good) cholesterol and high triglycerides

- History of gestational diabetes (diabetes during pregnancy), heart disease, stroke, polycystic ovarian syndrome, depression, or acanthosis nigricans

NUTRITION GUIDELINES

Key recommendations from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) nutritional guidelines include:

- Your eating plan should be individualized to accommodate your unique health profile. For nutritional advice, consult a dietitian or participate in a diabetes self-management education program.

- The ADA no longer has general recommendations for the percentage of daily calories that carbohydrates, fats, or protein should comprise. Those percentages need to be individually determined for each person.

- There is no evidence that any specific eating plan (Mediterranean, vegetarian, or low-carb) is better than another. What is most important is to find a plan that best suits your lifestyle and food preferences.

VACCINATION RECOMMENDATION

The CDC now recommends that adults ages 19 to 59 years diagnosed with diabetes should receive vaccinations to prevent hepatitis B. The hepatitis B virus is transmitted through blood, semen, or other body fluids. Unvaccinated people with diabetes can become infected with hepatitis B through sharing fingerstick devices, blood glucose monitoring devices, or insulin pens. Other vaccines that may be recommended to adults with diabetes include the influenza, pneumococcal, Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis), and zoster vaccines.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a long-term (chronic) disease in which either the pancreas production of insulin is insufficient or the response of the body to insulin is impaired. As a result, the body is unable to metabolize carbohydrates properly, and the level of glucose (sugar) in the blood is increased.

The two major forms of diabetes are type 1 (previously called insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, IDDM, or juvenile-onset diabetes) and type 2 (previously called noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, NIDDM, or adult-onset diabetes).

In type 2 diabetes, the body is insulin resistant: you need high levels of insulin to keep blood sugars normal and the pancreas can't make enough insulin. In type 1 diabetes, the body does not make any insulin or does not produce enough of it.

INSULIN

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes share one central feature of elevated blood sugar (glucose) level due to insufficiencies of insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas. Insulin is a key regulator of the body's metabolism. It works in the following way:

- During and immediately after a meal, the process of digestion breaks down carbohydrates into sugar molecules (including glucose) and proteins into amino acids.

- Right after the meal, glucose and amino acids are absorbed directly into the bloodstream, and blood glucose levels rise sharply.

- The rise in blood glucose levels signals important cells in the pancreas, called beta cells, to secrete insulin, which pours into the bloodstream. Within 10 minutes after a meal, insulin rises to its peak level.

- Insulin enables glucose to enter cells in the body, particularly muscle and fat cells. Here, insulin and other hormones direct whether glucose will be burned for energy or stored for future use. Insulin is also important in telling the liver how to process glucose.

- When insulin levels are high, the liver stops producing glucose and stores it in other forms until the body needs it again.

- As blood glucose levels start to come down after a meal, the pancreas reduces the production of insulin.

- Two to four hours after a meal, both blood glucose and insulin are back at low levels. The blood glucose levels are then referred to as preprandial blood glucose concentrations.

The pancreas is located below and behind the stomach and is where the hormone insulin is produced. Insulin is used by the body to store and use glucose.

TYPE 2 DIABETES

Type 2 diabetes is the most common form of diabetes, accounting for 90% of people with diabetes. In type 2 diabetes, the body does not respond properly to insulin, which means the insulin signal becomes too weak, a condition known as insulin resistance. Over time, the pancreas also becomes unable to produce inulin in adequate amounts to keep the blood sugar normal. The disease process of type 2 diabetes involves:

- The first stage in type 2 diabetes is insulin resistance. Although insulin can attach normally to receptors on fat and muscle cells, the hormone becomes less effective at triggering the mechanisms inside the cell that allow glucose to enter and be burned for fuel or stored. In the liver, insulin resistance causes the liver to make and release too much glucose into the blood. Most people with type 2 diabetes initially produce normal or even high amounts of insulin, and the insulin is enough to normally regulate blood sugar. In the beginning, this amount of insulin is usually enough to overcome insulin resistance.

- Over time, the pancreas becomes unable to produce enough insulin to overcome resistance. In type 2 diabetes, the initial effect of this stage is usually an abnormal rise in blood sugar after a meal (called postprandial hyperglycemia or impaired glucose tolerance [IGT]).

- Eventually, the cycle of elevated glucose further damages beta cells, thereby drastically reducing insulin production and causing full-blown diabetes. This is made evident by fasting hyperglycemia, in which glucose levels are high, even early in the morning before eating breakfast (called impaired fasting glucose or IFG).

- Finally, as beta cell insulin production decreases even more you develop full type 2 diabetes.

TYPE 1 DIABETES

In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas does not produce insulin. Type 1 diabetes is considered an autoimmune disorder. The condition is usually first diagnosed in childhood or adolescence but can occur at any age. People with type 1 diabetes need to take daily insulin for survival. About 5% of people with diabetes have Type 1 diabetes.

GESTATIONAL DIABETES

Gestational diabetes is a form of type 2 diabetes, usually temporary, that first appears during pregnancy. It usually develops during the third trimester of pregnancy. After delivery, blood sugar (glucose) levels generally return to normal, although women who had gestational diabetes are at higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes over time.

Because glucose crosses the placenta, a pregnant woman with diabetes can pass high levels of blood glucose to the fetus. This can cause excessive fetal weight gain, which can cause complications during delivery as well as increased risk of breathing problems.

Children born to women who have gestational diabetes have an increased risk of developing obesity and type 2 diabetes. In addition to endangering the fetus, gestational diabetes is also associated with serious health risks for the mother, such as preeclampsia, a condition that involves high blood pressure during pregnancy.

OTHER TYPES OF DIABETES

- MODY (maturity onset diabetes of the young) -- diabetes caused by inheritance of a single gene defect, most commonly a transcription factor or enzyme involved in regulating insulin production. The disease resembles type 2 diabetes, but people are younger, weigh less, and have a strong family history of diabetes at a young age. (Also known as monogenic diabetes syndromes.)

- Familial partial lipodystrophy -- inheritance of a defect of development of fat tissue. People with this kind of diabetes have muscular legs and glutes, but significant abdominal and truncal obesity. Many have fatty liver and high cholesterol levels. Similar to type 2 diabetes, but often diagnosed at a younger age.

- Long-term (chronic) pancreatitis -- diabetes caused by damage to the exocrine pancreas often from alcohol intake or gallstones. The beta cells in the pancreas also get damaged over time. Similar to type 2 diabetes, but people weigh less and have history of episodes of severe abdominal pain.

- Others include PCOS (see below), hemochromatosis (iron overload), cystic fibrosis, Cushing's disease, acromegaly, some medications (see below), and many other genetic syndromes.

Causes

Type 2 diabetes is caused by insulin resistance, in which the body does not properly use insulin. Type 2 diabetes is thought to result from a combination of genetic factors along with lifestyle factors, such as:

- Obesity

- Poor diet

- High alcohol intake

- Being sedentary

Genetic mutations likely affect parts of the insulin signaling pathway and various other physiologic components involved in the regulation of blood sugar. Type 2 diabetes often runs in the family. Multiple gene mutations that each have a fairly weak effect alone are often involved, but together increase the risk of developing the disease.

TYPE 2 DIABETES SECONDARY TO MEDICATIONS

High doses of statin drugs, which are used to lower cholesterol levels, may increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Some types of drugs can also cause temporary diabetes, including:

- Corticosteroids

- Beta blockers

- Phenytoin

- Anti-psychotic medications (see below)

Risk Factors

More than 29 million American children and adults have diabetes. About 90% of people with diabetes have type 2 diabetes. In addition, 86 million American adults have prediabetes, a condition that increases the risk for developing diabetes. About 1 in 4 Americans that have diabetes do not know they have it, because they have not seen a provider or have not been tested. Diabetes rates have been increasing among both adults and children.

Risk factors that strongly increase the risk for diabetes or prediabetes include:

- A previous diabetes test showing impaired fasting glucose (IFG) or IGT

- Age 45 years or older

- Family history of diabetes

- Being overweight or obese

- Inactive lifestyle (exercise less than 3 times a week)

- African-American, Hispanic/Latin American, American Indian and Alaska Native, Asian-American, or Pacific Islander ethnicity

- High blood pressure (140/90 mm Hg or higher)

- HDL (good) cholesterol less than 35 mg/dL or triglyceride level 250 mg/dL or higher

- Women who had diabetes during pregnancy (gestational diabetes) or gave birth to a baby that weighed more than 9 pounds (4 kilograms)

- History of heart disease, stroke, depression, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or acanthosis nigricans

MEDICAL CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH INCREASED RISK OF DIABETES

Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome

Obesity is the number one risk factor for type 2 diabetes. About 85% of people with type 2 diabetes are overweight or obese. Excess body fat plays a strong role in insulin resistance, but the way the fat is distributed is also significant.

Weight concentrated around the abdomen and in the upper part of the body (apple-shaped) is associated with:

- Insulin resistance and diabetes

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Stroke

- Unhealthy cholesterol levels

- More inflammation in the body

Waist circumferences greater than 35 inches (89 centimeters) in women and 40 inches (101 centimeters) in men are specifically associated with a greater risk for heart disease and diabetes (these values are specific to ancestry - and are lower if your ancestry is Asian). People with a "pear-shape", fat that settles around the hips, glutes, and things, appear to have a lower risk for these conditions, but the risk is still higher than if you are not obese. Obesity does not explain all cases of type 2 diabetes.

Metabolic syndrome is a prediabetic condition that is significantly associated with heart disease and higher mortality rates from all causes. The syndrome consists of:

- Abdominal obesity

- Unhealthy cholesterol and triglyceride levels

- High blood pressure

- Insulin resistance

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

PCOS is a condition that affects about 6% of women and results in the ovarian production of high amounts of androgens (male hormones), particularly testosterone. Women with PCOS are at higher risk for insulin resistance, and about half of the people with PCOS also have diabetes.

Acanthosis

Acanthosis is a skin condition in which dark and thickened patches of skin develop in areas of folds and creases such as the armpits, groin, and neck. This condition is often associated with type 2 diabetes but can also appear in other disorders characterized by insulin resistance, as well as certain genetic diseases or cancers.

Depression

Severe clinical depression may modestly increase the risk for type 2 diabetes. In addition, type 2 diabetes also increases the risk of depression.

Schizophrenia

While no definitive association has been established, research has suggested an increased background risk of diabetes among people with schizophrenia. In addition, many antipsychotic medications can elevate the blood glucose level. People taking atypical antipsychotic medications (clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, aripiprazole, quetiapine fumarate, and ziprasidone) should receive a baseline blood glucose level test and be monitored for any increases during therapy, especially if the medication results in weight gain.

GESTATIONAL DIABETES RISK FACTORS

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a type of diabetes that develops during the last trimester of pregnancy. A pregnant woman's risk factors include:

- Family history of diabetes

- African-American, Hispanic, Asian, or Pacific Islander ethnicity

- Being overweight or obese

- Age older than 25 years

- Gestational diabetes with previous pregnancy

- Having given birth to a child weighing over 9 pounds (4 kilograms)

- Diagnosis of prediabetes

Women who have gestational diabetes are at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes after their pregnancy. Guidelines recommend that women without diabetes symptoms should be screened for gestational diabetes at 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy.

Women with risk factors for diabetes may be screened for GDM earlier in the pregnancy. They should also be tested for undiagnosed type 2 diabetes at the first prenatal visit.

Women diagnosed with GDM should be screened for persistent diabetes 6 to 12 weeks after giving birth and should be sure to have regular screenings at least every 3 years afterward.

Symptoms

Type 2 diabetes usually begins gradually and progresses slowly. Symptoms in adults include:

- Excessive thirst

- Increased urination, particularly at night

- Fatigue

- Blurred vision

- Weight loss

- In women, vaginal yeast infections or fungal infections under the breasts or in the groin

- Severe gum problems

- Problems with wound healing

- Itching

- Erectile dysfunction in men

- Unusual sensations, such as tingling or burning, in the extremities

Symptoms in children are often different:

- Most children are obese or overweight

- Increased urination is mild or even absent

- Many children develop a skin problem called acanthosis, characterized by velvety, darker-colored patches of skin in the neck folds or armpits

Complications

People with diabetes have higher death rates than people who do not have diabetes, regardless of sex, age, or other factors. Heart disease and stroke are the leading causes of death in these people. All lifestyle and medical efforts should be made to reduce the risk for these conditions.

People with type 2 diabetes are also at risk for nerve damage (neuropathy) and abnormalities in both small and large blood vessels (vascular injuries) that occur as part of the diabetic disease process. Such abnormalities produce complications over time in many organs and structures in the body. Although these complications tend to be more serious in type 1 diabetes, they still are of concern in type 2 diabetes.

HEART DISEASE

There is an association between high blood pressure (hypertension), unhealthy cholesterol level, and diabetes. People with diabetes are more likely than non-diabetics to have heart problems, and to die from cardiovascular complications, including heart attack and stroke.

Diabetes affects the heart in many ways:

- Both type 1 and 2 diabetes speed the progression of atherosclerosis (deposition of fat inside arteries), which is a major risk factor for heart disease and stroke. Diabetes is often associated with low HDL (good cholesterol) and high triglycerides. This can lead to coronary artery disease, heart attack, or stroke.

- High blood pressure is more common in people with diabetes than those without the condition.

- Impaired nerve function (neuropathy) associated with diabetes may also lead to heart problems.

- Women with diabetes are at particularly high risk for heart problems and death from heart disease and overall causes. Women are more likely to have atypical symptoms of heart disease.

KIDNEY DAMAGE (NEPHROPATHY)

Kidney disease (nephropathy) is a very serious complication of diabetes. With this condition, the tiny filters in the kidney (called glomeruli) become damaged and leak protein into the urine. Over time, this can lead to kidney failure. Urine tests showing microalbuminuria (small amounts of protein in the urine) are important markers for kidney damage. Medications can slow the progression of kidney disease if it is caught early.

Diabetic nephropathy is the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). If the kidneys fail, dialysis is required. Symptoms of kidney failure may include:

- Swelling in the feet and ankles

- Itching

- Fatigue

- Pale skin color

NERVE DISORDERS (NEUROPATHY)

Diabetes reduces or distorts nerve function, causing a condition called neuropathy. Neuropathy refers to a group of disorders that affect peripheral nerves. The main types of neuropathy are:

- Sensory. Affects nerves in the toes, feet, legs, hand, and arms.

- Autonomic. Affects nerves that help regulate digestive, bowel, bladder, heart, and sexual function. Also controls the sweat glands in the feet.

- There are also motor neuropathy and joint neuropathy (see arthropathy below) problems that develop due to diabetes.

Peripheral neuropathy particularly affects sensation. It is a common complication for nearly half of people that have lived with type 1 or type 2 diabetes for more than 25 years. The most serious consequences of neuropathy occur in the legs and feet and pose a risk for skin wounds (called ulcers) which, in severe cases, can lead to amputation. Peripheral neuropathy usually starts in the fingers and toes and moves up to the arms and legs (called a stocking-glove distribution). Symptoms include:

- Tingling

- Weakness

- Burning sensations

- Loss of the sense of warm or cold

- Numbness (if the nerves are severely damaged, the person may be unaware that a blister or minor wound has become infected)

- Deep pain

Autonomic neuropathy can cause:

- Dry cracked skin on your feet.

- Digestive problems (constipation, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting).

- Bladder infections and incontinence.

- Erectile dysfunction.

- Heart problems. Neuropathy may mask angina, the warning chest pain for heart disease and heart attack. People with diabetes should be aware of other warning signs of a heart attack, including sudden fatigue, sweating, shortness of breath, nausea, and vomiting.

- Rapid heart rates.

- Lightheadedness when standing up (orthostatic hypotension).

Heart disease risk factors may increase the likelihood of developing neuropathy. Lowering triglycerides, losing weight, reducing blood pressure, and quitting smoking may help prevent the onset of neuropathy.

FOOT ULCERS AND AMPUTATIONS

About 15% of people with diabetes have serious foot problems. They are the leading cause of hospitalizations for these people.

Diabetes is responsible for more than half of all lower limb amputations performed in the US. Most amputations start with foot ulcers.

Those most at risk are people with a long history of diabetes, and people with diabetes who are overweight or who smoke. People who have the disease for more than 20 years are at the highest risk. Related conditions that put people at risk include:

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Peripheral artery disease (PAD)

- Foot deformities, such as hammer toes

- A history of ulcers

Foot ulcers usually develop from small cuts or abrasions that become infected, such as those resulting from blood vessel injury. Foot infections often develop from injuries, which can dramatically increase the risk for amputation. Even minor infections can develop into severe complications. Neuropathy which causes numbness is the biggest risk factor. Numbness from nerve damage, which is common in diabetes, compounds the danger since the person may not be aware of injuries. About a third of foot ulcers occur on the big toe. Damage to blood vessels that decrease blood flow to the injured area can also contribute to the risk of ulcers.

Charcot Foot

Charcot foot or Charcot joint (medically referred to as neuropathic arthropathy) is a degenerative condition that affects the bones and joints in the feet. It is associated with the nerve damage that occurs with neuropathy. Early changes appear similar to an infection, with the foot becoming swollen, red, and warm. Gradually, the affected foot can become deformed. The joints may shift, change shape, and become unstable. Bone damage can also result.

It typically develops in people who have neuropathy to the extent that they cannot feel sensations in their foot and are not aware of an existing injury. Instead of resting an injured foot or seeking medical help, the person often continues normal activity, causing further damage.

People with diabetes are prone to foot problems because the disease can cause damage to the nerves and blood vessels, which may result in decreased ability to sense trauma to the foot. The immune system is also altered (particularly if blood sugar levels are not well controlled), so that the person cannot efficiently fight infection.

RETINOPATHY AND EYE COMPLICATIONS

Diabetes accounts for thousands of new cases of blindness annually and is the leading cause of new cases of blindness in adults ages 20 to 74 years. The most common eye disorder in diabetes is retinopathy. People with diabetes are also at higher risk for developing cataracts and certain types of glaucoma, such as primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG). The risk for POAG is high for women with type 2 diabetes.

Retinopathy is a condition in which the retina in the eye becomes damaged. Retinopathy is the most common complication of diabetes, and generally occurs in one or two phases:

- The early and more common type of this disorder is called nonproliferative or background retinopathy. The blood vessels in the retina are abnormally weakened. They rupture and leak, and waxy areas may form on the retina. If these processes affect the central portion of the retina, swelling may occur, causing reduced or blurred vision - this is called macular edema.

- If the capillaries become blocked and blood flow is cut off, soft, "woolly" areas may develop in the retina's nerve layer. These woolly areas may signal the development of proliferative retinopathy. In this more severe condition, new abnormal blood vessels form and grow on the surface of the retina. They may spread into the cavity of the eye or bleed into the back of the eye. Major hemorrhage or retinal detachment can result, causing severe visual loss or blindness. The sensation of seeing flashing lights may indicate retinal detachment.

- Regular eye exams that check the retina can detect retinopathy at an early stage when it can be treated.

MENTAL FUNCTION AND DEMENTIA

Some studies indicate that people with type 2 diabetes, particularly those who have severe instances of low blood sugar, face a higher than average risk of developing dementia. Diabetes can also cause problems with attention and memory.

INFECTIONS

Respiratory Infections

People with diabetes face a higher risk for influenza and its complications, including pneumonia. Everyone with diabetes should have annual influenza vaccinations and a vaccination against pneumococcal pneumonia.

People with diabetes are at higher risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Risk of needing to be in the hospital and dying from COVID-19 is about three times higher than for people without diabetes. Obesity may also be an independent risk factor. The biggest increase in risk due to diabetes is for patients with higher blood sugar levels (A1C above 10%).

Urinary Tract Infections

Women with diabetes face a significantly higher risk for urinary tract infections, which are likely to be more complicated and difficult to treat than in the general population.

Hepatitis

People with diabetes are at increased risk for contracting the hepatitis B virus, which is transmitted through blood and other bodily fluids. Exposure to the virus can occur through sharing fingerstick devices or blood glucose monitors. Adults newly diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes should get hepatitis B vaccinations.

Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infection

Aggressive, rapidly progressive soft tissue infections below the skin may occur. They often occur in the groin area (called Fournier's gangrene), but can also be on the legs or abdominal wall.

DEPRESSION

Diabetes doubles the risk for depression. Depression, in turn, may increase the risk for high blood sugar level (hyperglycemia) and the complications of diabetes.

HYPOGLYCEMIA

Tight blood sugar (glucose) control increases the risk of low blood sugar (hypoglycemia). Hypoglycemia, also called insulin shock, occurs if blood glucose level falls below normal. It is generally defined as a blood sugar level below 70 mg/dL, although this level may not necessarily cause symptoms in all people. People with frequent hypoglycemia may not sense the low blood sugar or only sense hypoglycemia very late. People who normally have high blood sugars may feel like they have hypoglycemia when they start taking medications and their blood sugars are actually in the normal range.

Hypoglycemia may also be caused by insufficient intake of food, excess exercise, or alcohol. Usually, the condition is manageable, but occasionally, it can be severe or even life-threatening, particularly if the person fails to recognize the symptoms, particularly while continuing to take insulin or other hypoglycemic drugs.

Mild hypoglycemia is common among people with type 2 diabetes, but severe episodes are rare, even among those taking insulin or sulfonylurea medications. Still, people who intensively control their blood sugar (glucose) level should be aware of warning symptoms.

Hypoglycemia symptoms: Mild symptoms usually occur at moderately low and easily correctable level of blood glucose. They include:

- Sweating

- Trembling

- Hunger

- Rapid heartbeat

- Lightheadedness or fainting

- Headache

Severely low blood glucose level can cause neurologic symptoms, such as:

- Confusion

- Weakness

- Disorientation

- Combativeness

- In rare and worst cases, coma, seizure, and death

[For information on preventing hypoglycemia or managing an attack, see Home Management section of this report.]

DIABETIC KETOACIDOSIS (DKA)

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a life-threatening complication caused by a complete (or almost complete) lack of insulin. In DKA, the body produces abnormally high levels of blood acids called ketones. Ketones are byproducts of fat breakdown that build up in the blood and appear in the urine. They are produced when the body burns fat instead of glucose for energy. The buildup of ketones in the body is called ketoacidosis. Extreme stages of DKA can lead to coma and death.

DKA is usually a complication of type 1 diabetes. In such cases, it is nearly always due to not adhering to your insulin treatment or an infection. However, DKA can also occur in people with type 2 diabetes, usually due to a serious infection or another severe illness.

HYPERGLYCEMIC HYPEROSOMOLAR SYNDROME (HHS)

Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome (HHS) is a serious complication of diabetes that involves a cycle of an increasing blood sugar level and dehydration, without high ketone levels (which makes it different from DKA). HHS usually occurs with type 2 diabetes, but it can also occur with type 1 diabetes. It is often triggered by a serious infection or another severe illness, or by medications that lower glucose tolerance or increase fluid loss; particularly in people who are not drinking enough fluids. It usually develops gradually over a few days and people become very dehydrated.

Symptoms of HHS include:

- High blood sugar level

- Dry mouth

- Extreme thirst

- Dry skin

- High fever

HHS can lead to loss of consciousness, seizures, coma, and death. HHS can be associated with acidosis, but this is usually lactic acidosis.

OTHER COMPLICATIONS

Diabetes increases the risk for developing other conditions, including:

- Hearing loss.

- Periodontal disease.

- Carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, also called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a particular danger for people who are obese.

- Cancers of the liver, pancreas, and endometrium and, to a lesser extent, colon and rectum, breast, and bladder.

- Fractures.

SPECIFIC COMPLICATIONS IN WOMEN

Diabetes can cause specific complications in women. Women with diabetes have an increased risk of recurrent yeast infections. In terms of sexual health, diabetes may cause decreased vaginal lubrication, which can lead to pain or discomfort during intercourse.

Although there is no evidence that oral contraceptives (birth control pills) increase a woman's risk for type 2 diabetes, women with diabetes should be aware that certain types of medication can affect their blood glucose level. For example, birth control pills can raise their blood glucose level. Long-term use (more than 2 years) of birth control pills may increase the risk of health complications. Thiazolidinedione drugs such as rosiglitazone (Avandia) and pioglitazone (Actos) can prompt renewed ovulation in premenstrual women who are not ovulating and can weaken the effect of birth control pills.

Diabetes and Pregnancy

Diabetes that occurs during pregnancy (gestational diabetes) and pregnancy in a person with existing diabetes can increase the risk for birth defects. A high blood sugar level (hyperglycemia) can affect the developing fetus during the critical first 6 weeks of organ development.

Women with diabetes (either type 1or type 2) who are planning on becoming pregnant should strive to maintain good glucose control for 3 to 6 months before pregnancy. Those who are overweight or obese should try to lose weight before becoming pregnant. It is also important for women to closely monitor their blood sugar level during pregnancy. For women with type 2 diabetes who take insulin, pregnancy can affect their insulin dosing needs. Insulin dosing may also need to be adjusted following delivery.

Diabetes and Menopause

The changes in estrogen and other hormonal levels that occur during perimenopause can cause major fluctuations in blood glucose level. Women with diabetes also face an increased risk of premature menopause, which can lead to higher risk of heart disease.

Diagnosis

Healthy adults age 45 years and older should get tested for diabetes every 3 years. People who have certain risk factors should ask their health care providers about testing at an earlier age and more frequently. These risk factors include:

- Being overweight or obese (BMI over 25), starting at age 35

- Sedentary lifestyle

- High blood pressure (greater than 140/90) or unhealthy cholesterol levels, particularly for people with low HDL (good) cholesterol and high triglyceride levels

- History of heart disease, stroke, or PAD

- A close relative (parent or sibling) with diabetes

- A high-risk ethnic group background (African-American, Latino, Native American, Asian American, or Pacific Islander)

- Having delivered a baby weighing over 9 pounds (4 kilograms) or having a history of gestational diabetes (in women)

- Polycystic ovary disease (in women)

- Acanthosis nigricans

Children and adolescents younger than 18 years should be tested for type 2 diabetes (even if they have no symptoms) if they are overweight or obese (BMI exceeding the 85th percentile for their age and sex) and have one or more of the diabetes risk factors above.

TESTING FOR DIABETES AND PREDIABETES

Prediabetes precedes the onset of type 2 diabetes. People who have prediabetes have a fasting blood glucose level that is higher than normal, but not yet high enough to be classified as diabetes. Prediabetes greatly increases the risk for diabetes. Depending on the test used for diagnosis, prediabetes is also called IFG or IGT (see above for definitions).

There are three tests that can be used to diagnose diabetes or identify prediabetes:

- Fasting plasma glucose (FPG)

- Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

- Hemoglobin A1C (A1C)

FASTING PLASMA GLUCOSE TEST

The FPG test is the standard test for diabetes. It is a simple blood test taken after 8 hours of fasting. FPG level indicates:

- Normal. Below 100 mg/dL.

- Prediabetes. Between 100 and 125 mg/dL.

- Diabetes.126 mg/dL or higher.

The FPG test is not always reliable, so a repeat test is recommended if the initial test suggests the presence of diabetes, or if the test is normal in people who have symptoms or risk factors for diabetes. Use of fingerstick blood glucose testing is not sufficient to make the diagnosis of diabetes.

ORAL GLUCOSE TOLERANCE TEST

The OGTT is more complex than the FPG and may over-diagnose diabetes in people who do not have it. Some providers recommend it as a follow-up after FPG, if the latter test results are normal but the person has symptoms or risk factors of diabetes. The test uses the following procedures:

- The person first has an FPG test.

- The person has a blood test 2 hours after drinking a special glucose solution.

OGTT level indicates:

- Normal. Below 140 mg/dL.

- Prediabetes. Between 140 and 199 mg/dL.

- Diabetes. 200 mg/dL or higher.

The person cannot eat for at least 8 hours prior to the FPG and OGTT tests.

Any random blood glucose of 200 mg/dL or higher, even without fasting, is also diagnostic of diabetes.

HEMOGLOBIN A1C TEST

This test examines blood levels of glycated hemoglobin, also known as hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c or A1C). The results are given in percentages and broadly reflect a person's average blood glucose level over the past 2 to 3 months. FPG and OGTT show a person's glucose level only at the time of the test. The A1C test is not affected by recent food intake so people do not need to fast to prepare for the blood test.

In addition to providing information on blood sugar control and effectiveness of diabetes treatment, the A1C test may also be used as an alternative test for diagnosing diabetes and identifying prediabetes.

A1C level indicates:

- Normal. Below 5.7%.

- Prediabetes. Between 5.7% and 6.4%.

- Diabetes. 6.5% or higher.

A1C tests are also used to help people with diabetes monitor how well they are keeping their blood glucose levels under control. For people with diabetes, A1C is measured periodically every 2 to 3 months, or at least twice a year. While fingerprick self-testing provides information on blood glucose for that day, the A1C test shows how well blood sugar has been controlled over the period of several months. In general, most people with diabetes should aim for an A1C level of around 7%. Your provider may adjust this goal depending on your individual health profile.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends that results from the A1C test be used to calculate the estimated average glucose (eAG). eAG is a term that people may see on lab results from their A1C tests. It converts the A1C percentages into the same mg/dL units that people are familiar with from their daily home blood glucose tests. This information is often misused (because each A1C can correspond to a wide range of average blood sugars), but when used correctly, the eAG terminology can help people to better interpret the results of their A1C tests and make it easier to correlate A1C with results from home blood glucose monitoring.

Certain conditions that affect hemoglobin molecules or the lifespan of red blood cells (such as sickle cell disease, hemodialysis, or others) may influence A1C results. In these cases, plasma glucose tests may be used instead.

SCREENING FOR GESTATIONAL DIABETES MELLITUS (GDM)

The ADA recommends screening for gestational diabetes that:

- Pregnant women

without

known risk factors for diabetes should be screened for gestational diabetes at 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy using the OGTT. - Pregnant women

with

risk factors for diabetes should be screened for type 2 diabetes at the first prenatal visit.

SCREENING TESTS FOR COMPLICATIONS

Screening for Heart Disease

People with diabetes should be:

- Tested for high blood pressure (hypertension)

- Tested for unhealthy cholesterol and lipid levels

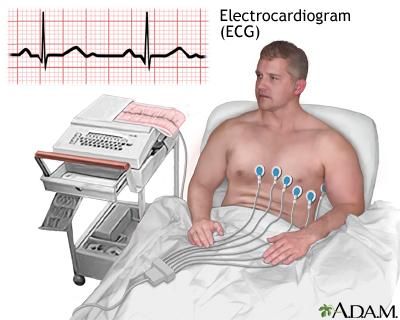

- Given an electrocardiogram

Other tests may be needed for people with signs of heart disease.

The electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) is used extensively in the diagnosis of heart disease, from congenital heart disease in infants to myocardial infarction and myocarditis in adults. Several different types of electrocardiogram exist.

Screening for Kidney Damage

The earliest manifestation of kidney damage is microalbuminuria, in which tiny amounts of a protein called albumin are found in the urine. Microalbuminuria typically shows up in people with type 2 diabetes who also have high blood pressure.

The ADA recommends that people with diabetes receive an annual urine test for albumin. During a period of poor blood glucose control, this test can overestimate the risk of kidney damage.

People with diabetes should also have their blood creatinine tested at least once a year. Creatinine is a waste product that is removed from the blood by the kidneys. A high level of creatinine may indicate kidney damage. A doctor uses the results from a creatinine blood test to calculate the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). GFR is an indicator of kidney function; it estimates how well the kidneys are cleansing the blood.

Screening for Retinopathy

The ADA recommends that people with type 2 diabetes get an initial comprehensive eye exam by an ophthalmologist or optometrist shortly after they are diagnosed with diabetes, and once a year thereafter. People at low risk may need follow-up exams only every 2 to 3 years.

The eye exam should include dilation of the pupil to check for signs of retinal disease (retinopathy). Instead of a comprehensive eye exam, fundus photography may be used as a screening tool. Fundus photography uses a special type of camera to take images of the back of the eye.

Screening for Neuropathy

People should be screened for nerve damage (neuropathy), including a comprehensive foot exam. People who lose sensation in their feet should have a foot exam every 3 to 6 months to check for ulcers or infections. People should also be screened for intermittent claudication and PAD using the ankle-brachial index for diagnosis.

Lifestyle Changes

Good nutrition and regular physical activity can help prevent or manage medical complications of diabetes (heart disease and stroke) and help people live longer and healthier lives.

DIET

There is no such thing as a single diabetes diet. People should meet with a professional dietitian to plan an individualized diet within the general guidelines that takes into consideration their own health needs. Diabetes self-management education programs can also provide valuable nutritional advice.

The ADA no longer advises a uniform ideal percentage of daily calories for carbohydrates, fats, or protein for all people with diabetes. Rather, these amounts should be individualized, based on your unique health profile.

Healthy eating habits along with good control of blood glucose are the basic goals, and several good dietary methods are available to meet them. Recommended eating plans include Mediterranean, vegetarian, and lower-carbohydrate diets. What is most important is to find a healthy eating plan that works best for you and your lifestyle and food preferences. Whatever eating plan you follow, try to eat a variety of nutrient-rich food in appropriate portion sizes.

The ADA's most recent nutritional guidelines for recommendations include:

- Choosing carbohydrates that come from vegetables, whole grains, fruits, beans (legumes), and dairy products. Avoid carbohydrates that contain added fats, sugar, or sodium.

- Choosing "good" fats over "bad" ones. The type of fat may be more important than the quantity. Monounsaturated (olive, peanut, and canola oils, avocados, and nuts) and omega-3 polyunsaturated (fish, flaxseed oil, and walnuts) fats are the best types of fats. Avoid unhealthy saturated fats (red meat and butter) and trans fats (hydrogenated fats found in snack foods, fried foods, and commercially baked goods).

- Choose protein sources that are low in saturated fat. Fish, poultry, legumes, and soy are better protein choices than red meat. Try to eat fatty fish, such as salmon and tuna, which are high in omega-3 fatty acids, at least twice a week.

- Limit intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, including those that contain high fructose corn syrup or sucrose. They are bad for your waistline and your heart.

- Sodium (salt) intake should be limited to 2,300 mg/day or less. People with diabetes and high blood pressure may need to restrict sodium even further. Reducing sodium can lower blood pressure and decrease the risk of heart disease and heart failure.

WEIGHT MANAGEMENT

Being overweight is the number one risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Even modest weight loss can help prevent type 2 diabetes from developing. It can also help control or even stop progression of type 2 diabetes in people with the condition and reduce risk factors for heart disease. People should lose weight if their body mass index (BMI) is 25 to 29 (overweight) or higher (obese).

The ADA recommends that overweight and obese people with diabetes who are ready to achieve weight loss aim for at least 5% weight loss over 6 months. Most people should follow a diet that supplies at least 1,000 to 1,200 kcal/day for women and 1,200 to 1,600 kcal/day for men. If short-term weight loss goals are achieved through diet and exercise, long-term weight maintenance programs are recommended.

People with type 2 diabetes who have a BMI greater than 35 and poor glycemic control, or those with a BMI greater than 40 regardless of glycemic control may consider having bariatric surgery to help improve their blood glucose levels.

EXERCISE

Sedentary habits, such as watching TV and sitting in front of a computer, are associated with significantly higher risks for obesity and type 2 diabetes. Regular exercise and physical activity, even of moderate intensity (brisk walking), improves insulin sensitivity and may play a role in preventing type 2 diabetes, regardless of weight loss.

Aerobic Exercise

Aerobic activity has significant and particular benefits for people with diabetes. Regular aerobic exercise, even of moderate intensity, improves insulin sensitivity. The heart-protective effects of aerobic exercise are also important, even if people have no risk factors for heart disease other than diabetes itself.

For improving blood sugar control, the ADA recommends at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity physical activity (50% to 70% of maximum heart rate) or at least 90 minutes per week of vigorous aerobic exercise (more than 70% of maximum heart rate). Exercise at least 3 days a week, and do not go more than 2 consecutive days without physical activity.

Strength Training

Strength training, which increases muscle and reduces fat, is also helpful for people with diabetes who are able to do this type of exercise. The ADA recommends performing resistance exercise three times a week. Build up to 3 sets of 8 to 10 repetitions using weight that you cannot lift more than 8 to 10 times without developing fatigue. Be sure that your strength training targets all of the major muscle groups.

Exercise Precautions

The following are precautions for all people with diabetes; both type 1 and type 2:

- Because people with diabetes are at higher than average risk for heart disease, they should always check with their providers before undertaking vigorous exercise. For fastest results, regular moderate to high-intensity (not high-impact) exercises are best for people who are cleared by their providers. For people who have been sedentary or have other medical problems, lower-intensity exercises are recommended.

- Strenuous strength training or high-impact exercise is not recommended for people with uncontrolled diabetes. Such exercises can strain weakened blood vessels in the eyes of people with retinopathy. High-impact exercise may also injure blood vessels in the feet.

People who are taking medications that lower blood glucose, particularly insulin or sulfonylurea drugs, should take special precautions before starting a workout program:

- Monitor glucose level before, during, and after workouts (glucose level swings dramatically during exercise).

- Avoid exercise if glucose level is above 300 mg/dL or under 100 mg/dL.

- Drink plenty of fluids before and during exercise.

- Before exercising, avoid alcohol and if possible certain drugs, including beta-blockers, which make it difficult to recognize symptoms of hypoglycemia.

- Insulin-dependent athletes may need to decrease insulin doses or take in more carbohydrates prior to exercise; they may need to take an extra dose of insulin after exercise (stress hormones released during exercise may increase blood glucose level).

- To help avoid hypoglycemia, inject insulin in sites away from the muscles used during exercise.

- Wear good, protective footwear to help avoid injuries and wounds to the feet.

- Some blood pressure drugs can interfere with exercise capacity. People who use blood pressure medication should talk to their providers about how to balance medications and exercise. People with high blood pressure should also aim to breathe as normally as possible during exercise. Holding your breath can increase blood pressure, particularly during strength training.

WARNING ON DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS

Various fraudulent products are often sold on the Internet as "cures" or treatments for diabetes. These dietary supplements have not been studied or approved. The FDA warns people with diabetes not to be duped by bogus and unproven remedies.

According to the ADA, there is no evidence to support any herbal remedies or dietary supplements (including fish oil supplements) for the treatment of diabetes. There is no evidence that vitamin or mineral supplements can help people with diabetes who do not also have underlying nutritional deficiencies.

Treatment

MANAGEMENT OF PREDIABETES

Treatment of prediabetes is very important. Lifestyle changes and medical interventions can help prevent, or at least delay, the progression to diabetes, as well as lower their risk for heart disease.

- The most important lifestyle treatment for people with prediabetes is to lose weight through diet and regular physical activity and exercise. Even a modest weight loss of 10 to 15 pounds (4 to 7 kilograms) can significantly reduce the risk of progressing to diabetes.

- People should have a physical activity goal of 90 minutes, at least 5 days a week, and follow nutritional guidelines that reduce calorie intake. A low-fat, high-fiber diet is often recommended, but no single diet is known to be better than any other. Quitting smoking is also essential.

- It is also important to have your doctor check your cholesterol and blood pressure levels on a regular basis. Your doctor should also check your fasting blood glucose and urine albumin levels every year, and your hemoglobin A1C and lipids every 6 months.

- In addition to lifestyle measures, the insulin-regulating drug metformin (Glucophage and generic) may be recommended for people who may be at very high risk for developing diabetes. High risk factors include an A1C of greater than 6%, high blood pressure, low HDL cholesterol, high levels of triglycerides, obesity, or family history of diabetes in a first-degree relative (parents, siblings, and children).

MANAGEMENT OF TYPE 2 DIABETES

The major treatment goals for people with type 2 diabetes are to control blood glucose level and to treat all conditions that place people at risk for heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, and other major complications.

Approaches to controlling blood glucose levels include:

- Achieving an A1C level less than 7%. People who have a history of severe hypoglycemia, vascular complications or other diseases, or longstanding diabetes may benefit from a less stringent A1C goal of 8%. Conversely, select people for whom a more stringent A1C goal of 6.5% can be achieved without adverse effects may include those with recent diabetes without complications, or without cardiovascular disease. People should discuss individualized treatment goals with their providers.

- Close monitoring of blood sugar and hemoglobin A1C levels.

- Lifestyle modifications (diet, exercise, and weight loss) are the first methods for improving blood glucose level. Weight loss of at least 5% achieved in the short term can be followed by long-term maintenance programs.

- If lifestyle modifications are not enough, the oral anti-hyperglycemic drug metformin is first recommended. A second drug may be added to metformin if necessary. Some people with type 2 diabetes may eventually require insulin.

- Bariatric surgery is recommended as an option for treatment for people with BMI higher than 35 who cannot achieve proper glycemic control with lifestyle and drug therapy.

Approaches for reducing complications include:

- Healthy lifestyle changes, such as regular exercise, heart-healthy diet, and quitting smoking.

- Use of various medications to control high blood pressure (ACE inhibitors and diuretics) and to lower cholesterol (statin drugs).

- Daily low-dose (75 to 162 mg) aspirin, recommended for men older than age 50 years and women older than age 60 years who have diabetes and at least one additional risk factor for heart disease (smoking, high blood pressure, unhealthy cholesterol levels, family history of heart disease, or albuminuria). Daily aspirin is not recommended for people with diabetes who are younger than these ages and who do not have cardiovascular risk factors.

- Maintaining close follow-up with your doctor.

Blood glucose goals before meals (normal is less than 100 mg/dL) are:

- Goal for adult is 80 to 130 mg/dL.

- Goal for children is about 90 to 130 mg/dL up to 180 mg/dL for children experiencing low blood sugar levels.

Peak postprandial goal is less than 180 mg/dL for adults and children.

Blood glucose goals at bedtime are:

- Less than 180 mg/dL for adults.

- 90 to 150 to 180 mg/dL for most children, but an ideal goal for each individual child should be set, and may depend on history of hypoglycemia, awareness of hypoglycemia, lifestyle, and other problems.

TREATING SPECIAL POPULATIONS

Different goals may be necessary for specific individuals, including:

- Pregnant women

- Very old and very young people

- Those with accompanying serious medical conditions

Treating children with type 2 diabetes depends on the severity of the condition at diagnosis. Metformin is approved for children. Formerly, only insulin was approved for treating children with diabetes.

The ADA does not recommend tight blood glucose control for children because glucose is necessary for brain development. Older people should not generally be placed on tight control as low blood sugar can increase the risk of stroke or heart attack. Tight control (A1C <7%) in older people taking medications that DO NOT cause hypoglycemia is not associated with higher risk and can be continued.

Treatment and Prevention of Complications

HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE AND HEART DISEASE

People with diabetes and high blood pressure should make lifestyle changes. These include:

- Losing weight (when needed).

- Following the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet.

- Quitting smoking.

- Limiting alcohol.

- Limiting salt to no more than 1,500 mg of sodium per day. Exact sodium limits are determined on an individual basis; discuss with your doctor what an appropriate sodium limit is for you.

Reducing blood pressure: In general, people with diabetes should strive for blood pressure levels of less than 140/90 mm Hg (systolic/diastolic). Lowering blood pressure to 130/80 mm Hg may be recommended for those at risk of cardiovascular disease. It is recommended that people with diabetes and hypertension monitor their blood pressure at home on a regular basis.

People with diabetes and high blood pressure need an individualized approach to drug treatment, based on their particular health profile. Dozens of anti-hypertensive drugs are available. The most beneficial fall into the following categories:

- Diuretics rid the body of extra sodium (salt) and water. There are three main types of diuretics: potassium-sparing, thiazide, and loop.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors reduce the production of angiotensin, a chemical that causes arteries to narrow.

- Angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) block angiotensin's action on arteries.

- Beta blockers block the effects of adrenaline and ease the heart's pumping action.

- Calcium-channel blockers (CCBs) decrease the contractions of the heart and widen blood vessels.

- SGLT2 inhibitors (Flozins) treat both diabetes and high blood pressure

Nearly all people who have diabetes and high blood pressure should take an ACE inhibitor as part of their regimen for treating hypertension. These drugs help prevent heart and kidney damage and are recommended as the best first-line drugs for people with diabetes and hypertension. An ARB is recommended for people who cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors.

Improving Cholesterol and Lipid Levels

Abnormal cholesterol and lipid levels are common in diabetes. High LDL (bad) cholesterol should always be lowered, but people with diabetes also often have additional harmful imbalances, including low HDL (good) cholesterol and high triglycerides.

In the past, the choices regarding when and how aggressively to treat hyperlipidemia was driven largely by your LDL and HDL cholesterol levels. However, scientific evidence to support the target number treatment approach is not very strong.

As a result, newer guidelines take, what is called, a risk-based approach when treating the person, rather than just treating the lab result. The intensity (dose) of the statin therapy is based on the risk for complications.

People with diabetes and:

- Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, should receive high-intensity statin therapy.

- Aged <40 years who also have other cardiovascular disease risk factors, should consider the use of moderate-intensity statin therapy

- Ages 40 to 75 years and >75 years without atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, should use moderate-intensity statin therapy.

For some people with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, if LDL cholesterol is >70 mg/dL on the highest statin dose that is tolerated, additional LDL-lowering therapy such as ezetimibe may be used.

Children should be treated for LDL cholesterol above 160 mg/dL, or above 130 mg/dL if other cardiovascular risk factors are present.

Lifestyle changes for cholesterol management in people with diabetes focus on:

- Reducing intake of saturated fats, trans fats, and dietary cholesterol

- Increasing intake of omega-3 fatty acids, viscous fiber, and plant stanols

- Weight loss if necessary

- Increased physical activity

For medications, statins are the best cholesterol-lowering drugs. They include:

- Atorvastatin (Lipitor and generic)

- Lovastatin (Mevacor and generic)

- Pravastatin (Pravachol and generic)

- Simvastatin (Zocor, Simcor, Vytorin, and generics)

- Fluvastatin (Lescol and generic)

- Rosuvastatin (Crestor)

- Pitavastatin (Livalo)

These drugs are very effective for lowering LDL cholesterol levels. However, they may increase blood glucose levels in some people, especially when taken in high doses. They may also increase the risk for developing type 2 diabetes in people who have risk factors. Still, statin drugs are considered generally safe. If one statin drug does not work or has side effects, the doctor may recommend switching to a different statin.

The primary safety concern with statins has involved myopathy, an uncommon condition that can cause muscle damage and, in some cases, muscle and joint pain. A specific myopathy called rhabdomyolysis can lead to kidney failure. People with diabetes and risk factors for myopathy should be monitored for muscle symptoms. Strategies for addressing the muscle side effects of statins include adjusting the dose of statin and switching to either another type of statin, combination, or non-statin lipid-lowering drugs.

Ezetimibe may be used in combination with a statin drug for those with recent acute coronary syndrome. A new type of medication called a PCSK9 inhibitor is now available to reduce cholesterol levels in people with genetic causes of high cholesterol levels. This medication is given as an injection under the skin.

Aspirin for Heart Disease Prevention

For people with diabetes who have additional heart disease risk factors, taking a daily aspirin can reduce the risk for blood clotting and may help protect against heart attacks. There is not enough evidence to indicate that aspirin prevention is helpful for people at lower risk. These risk factors include:

- A family history of heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Smoking

- Unhealthy cholesterol levels

- Excessive urine levels of the protein albumin

The recommended dose is 75 to 162 mg/day. Talk to your doctor, particularly if you are at risk for aspirin side effects such as gastrointestinal bleeding and ulcers.

Surgery for Heart Disease

People with heart disease that has caused blockage in the arteries, angina (chest pain), and other symptoms may require surgery. The two main types of surgical procedures are percutaneous coronary intervention (commonly called PCI or angioplasty) with stenting and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Although PCI and stenting are less invasive than CABG, recent research indicates that CABG is safer and works better for people with diabetes who have multiple blockages in their arteries.

TREATMENT OF RETINOPATHY

People with severe diabetic retinopathy or macular edema (swelling of the retina) should be sure to see an eye specialist who is experienced in the management and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Once damage to the eye develops, laser or photocoagulation eye surgery may be needed. Laser surgery can help reduce vision loss in high-risk people. Drug therapy with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is also recommended for treatment of diabetic macular edema.

TREATMENT OF FOOT ULCERS

About a third of foot ulcers will heal within 20 weeks with good wound care treatments. Some treatments are as follows:

- Antibiotics are generally given. In some cases, hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics for up to 28 days may be needed for severe foot ulcers and for people who have peripheral artery disease (PAD).

- In virtually all cases, wound care requires debridement, the removal of injured tissue until only healthy tissue remains. Debridement may be accomplished using chemical (enzymes), surgical, or mechanical (irrigation) means.

- Hydrogels (NU-GEL) may help to soothe and heal ulcers.

- Felted foam may help heal ulcers on the sole of the foot. Felted foam uses a multi-layered foam pad over the bottom of the foot with an opening over the ulcer.

Other Treatments for foot ulcers: Doctors are also using or investigating other treatments to heal ulcers. These include:

- Administering hyperbaric oxygen (oxygen given at high pressure) is generally reserved for people with severe, full thickness diabetic foot ulcers, particularly when gangrene or an abscess is present, that have not responded to other treatments. It is not recommended for an infection in the bone (osteomyelitis). Its usefulness or benefit is not well proven or accepted.

- Total-contact casting (TCC), which uses a cast that is designed to match the exact contour of the foot and distribute weight along the entire length of the foot. It is usually changed weekly. It may be helpful for ulcer healing and for Charcot foot. Although it is very effective in healing ulcers, recurrence is common.

- Other devices such as cast walkers and shoe modifications that offload the weight and pressure over an area may be used.

TREATMENT OF DIABETIC NEUROPATHY

The only FDA-approved drugs for treating neuropathy are pregabalin (Lyrica) and duloxetine (Cymbalta). Other drugs and treatments are used on an off-label basis.

The American Academy of Neurology's (AAN) guidelines for treating painful diabetic neuropathy recommend:

Anticonvulsants.

Pregabalin (Lyrica) is a first-line treatment and has the strongest evidence for efficacy of all neuropathy treatments. Gabapentin (Neurontin and generic) and valproate (Depaco and generic) may also be considered.Antidepressants.

Duloxetine (Cymbalta) and venlafaxine (Effexor) are recommended, as is amitriptyline (Elavil and generic). Venlafaxine may be given in combination with gabapentin. Duloxetine and venlafaxine are serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant. Tricyclics may cause heart rhythm problems, so people at risk need to be monitored carefully.Opioids.

Opioids are powerful prescription narcotic painkillers. Morphine, oxycodone, and tramadol (Ultram and generic) may be considered for severe neuropathy pain. These drugs can cause significant side effects (nausea, constipation, and headache) and are highly addictive, so benefits should be weighed against these risks, the treatment closely monitored, and decisions made together with the person.Topical Medications.

Capsaicin ointment or a lidocaine skin patch may be effective. These treatments are applied directly to the skin. Capsaicin is the active ingredient in hot chili peppers.

Non-drug treatments

Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS) may help some people. PENS uses electrodes attached to precisely placed acupuncture-type needles to deliver electrical current to peripheral sensory nerves. Doctors also recommend lifestyle measures, such as walking and wearing elastic stockings.

Treatments for other complications of neuropathy

Neuropathy also impacts other functions, and treatments are needed to reduce their effects. If diabetes affects the nerves in the autonomic nervous system, then abnormalities of blood pressure control and bowel and bladder function may occur. Erythromycin, domperidone (Motilium), or metoclopramide (Reglan) may be used to relieve delayed stomach emptying caused by neuropathy. People need to watch their nutrition if the problem is severe.

Erectile dysfunction is also associated with neuropathy

Studies indicate that phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE-5) drugs, such as sildenafil (Viagra), vardenafil (Levitra), tadalafil (Cialis), and avanafil (Stendra) are safe and effective, at least in the short term, for many people with diabetes. People who take nitrate medications for heart disease cannot use PDE-5 drugs.

TREATMENT OF KIDNEY PROBLEMS

Good control of blood sugar and blood pressure is essential for preventing the onset of kidney disease and for slowing the progression of the disease.

ACE inhibitors are the best class of blood pressure medications for delaying kidney disease and slowing disease progression in people with diabetes. ARBs are also very helpful. The calcium channel blockers diltiazem and verapamil can also reduce protein excretion by diabetic kidneys.

- For people with diabetes who have microalbuminuria, the ADA strongly recommends ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Microalbuminuria is an accumulation of protein in the urine, which can signal the onset of kidney disease (nephropathy).

- Nearly all people who have diabetes and high blood pressure should take an ACE inhibitor (or ARB) as part of their regimen for treating their hypertension.

Anemia

Anemia is a common complication of end-stage kidney disease. People on dialysis usually need injections of erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs to increase red blood cell counts and control anemia. However, these drugs, including darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp) and epoetin alfa (Epogen and Procrit), can increase the risk of blood clots, stroke, heart attack, and heart failure in people with end-stage kidney disease when they are given at higher than recommended doses.

The FDA recommends that people with end-stage kidney disease who receive erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs should:

- Maintain hemoglobin levels between 10 to 12 g/dL.

- Receive frequent blood tests to monitor hemoglobin levels.

- Contact their providers if they experience such symptoms as shortness of breath, pain, swelling in the legs, or increases in blood pressure.

Medications

Many types of anti-hyperglycemic drugs are available to help people with type 2 diabetes control their blood sugar levels. Most of these drugs are aimed at increasing sensitivity to the person's own natural stores of insulin or boosting the person's own insulin production. Guidelines for the optimal use of these medications are changing rapidly.

Older oral hypoglycemic drugs, particularly metformin, are less expensive and generally work as well as newer diabetes drugs. Metformin is usually recommended as the first-line drug.

Adding a second oral hypoglycemic drug may be recommended if adequate control is not achieved with the first medication. For the most part, providers should add a second drug rather than trying to push the first drug dosage to the highest levels.

BIGUANIDES (METFORMIN)

Metformin (Glucophage and generic) is a biguanide, which works by reducing glucose production in the liver and by making tissues more sensitive to insulin. Providers recommend it as a first choice for most people with type 2 diabetes. Metformin may also be used in combination with other drugs.

Metformin does not cause hypoglycemia or add weight, so it is particularly well suited for people who are obese with type 2 diabetes. Metformin also appears to have beneficial effects on cholesterol and lipid levels and may help protect the heart. It is also the first choice for children who need oral drugs.

Side effects may include:

- A metallic taste.

- Gastrointestinal problems, including nausea and diarrhea (common, often improves over time or with lower doses).

- Interference with the absorption of vitamin B12 and folic acid.

- Lactic acidosis is a rare potentially life-threatening side effect. Major studies, however, have found no greater risk with metformin than with any of the other drugs used for type 2 diabetes.

Certain people should not use this drug, including anyone with certain kinds of heart failure or kidney or severe liver disease. Kidney disease and gastrointestinal side effects are the main reason for stopping this medication.

SULFONYLUREAS

Sulfonylureas are oral drugs that stimulate the pancreas to release insulin. These medications were the second line diabetes treatment for years, but this is changing because they are more likely to cause weight gain and low blood sugar. A number of brands are available including chlorpropamide (Diabinese and generic), tolazamide (Tolinase and generic), glipizide (Glucotrol and generic), tolbutamide (Orinase and generic), glyburide (Micronase and generic), and glimepiride (Amaryl and generic). For adequate control of blood glucose levels, the drugs should be taken 20 to 30 minutes before a meal.

Most people can take sulfonylureas for 7 to 10 years before they lose effectiveness. Combinations with small amounts of insulin or other oral anti-hyperglycemic drugs (metformin or a thiazolidinedione) may extend their benefits. A combination of glyburide and metformin in 1 pill (Glucovance) is available.

Side Effects and Complications

In general, women who are pregnant or nursing or individuals who are allergic to sulfa drugs should not use sulfonylureas. Side effects may include:

- Hypoglycemia is the most common side effect. It is more likely with chlorpropamide and glyburide because they stay in your body for a longer period of time. Care should be taken during and after exercise.

- Weight gain (some sulfonylureas, such as glimepiride, may produce less weight gain than others)

- Water retention

- Some sulfonylureas may pose a slight risk for cardiac events.

- Although sulfonylureas pose a lower risk for hypoglycemia than insulin does, the hypoglycemia produced by sulfonylureas may be especially prolonged and dangerous. The newer sulfonylureas, such as glimepiride, have much less risk of hypoglycemia than older sulfonylureas.

- Some sulfonylureas may pose a slight risk for cardiac events.

Sulfonylureas interact with many other drugs, and people must inform their provider of any medications they are taking, including over-the-counter drugs or herbal supplements.

MEGLITINIDES

Meglitinides stimulate beta cells to produce insulin. They include repaglinide (Prandin) and nateglinide (Starlix and generic). These drugs are rapidly metabolized and short-acting and therefore have a lower risk of hypoglycemia. If taken before every meal, they tend to mimic the normal effects of insulin after eating. People, then, can vary their meal times with this drug. These drugs often used in combination with metformin or other drugs.

Side Effects

Side effects include diarrhea and headache. As with the sulfonylureas, repaglinide poses a slightly increased risk for cardiac events. Newer drugs, such as nateglinide, may pose less of a risk. People with heart failure or liver disease should use them with caution and be monitored.

THIAZOLIDINEDIONES

Thiazolidinediones, also known as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonists, include pioglitazone (Actos and generic) and rosiglitazone (Avandia). Thiazolidinediones are taken as pills, usually in combination with other oral drugs or insulin. Thiazolidinediones available as 2-in-1 pills include rosiglitazone and metformin (Avandamet), rosiglitazone and glimepiride (Avandaryl), pioglitazone and metformin (ACTOPLUS MET), and pioglitazone and glimepiride (Duetact). These are the most powerful medication to increase insulin sensitivity in the liver.

Side Effects

Thiazolidinediones can have serious side effects. They can increase fluid build-up, which can cause or worsen heart failure in some people and often leads to water retention and swelling (edema) in the feet and legs. Combinations with insulin increase the risk. People with heart failure should not use them. People with risk factors for heart failure should use these drugs with caution.

In particular, there have been concerns that rosiglitazone increases the risks for heart attack and heart failure and should be restricted to only certain people. In 2013, the FDA lifted these restrictions, citing studies that indicated the drug posed no heightened risk for heart attack or death.

Thiazolidinediones may cause more weight gain than other diabetes medications or insulin. Any person who has sudden weight gain, water retention, or shortness of breath should immediately call their provider. Thiazolidinediones can also cause liver damage. People who take these drugs should have their liver enzymes checked regularly.

Other health concerns associated with thiazolidinediones included possible increased risks for:

- Bone fracture

- Bladder cancer

- Development or worsening of the eye condition diabetic macular edema

ALPHA-GLUCOSIDASE INHIBITORS

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, including acarbose (Precose and generic) and miglitol (Glyset), reduce glucose levels by interfering with the absorption of starch in the small intestine. Acarbose tends to lower insulin levels after meals, a particular advantage, since higher levels of insulin after meals are associated with an increased risk for heart disease.

Because this class of drugs does not work as well as others, they are not preferred second-line treatments.

Side Effects

These medications need to be taken with meals. Unfortunately, about a third of people stop taking the drug because of flatulence and diarrhea, particularly after high-carbohydrate meals. The drug may also interfere with iron absorption.

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors do not cause hypoglycemia when used alone, but combinations with other drugs do. In such cases, it is important that the person receives a solution that contains glucose or lactose, not table sugar. This is because acarbose inhibits the breakdown of complex sugar and starches, which includes table sugar.

GLP-1 MIMETICS (EXENATIDE, LIRAGLUTIDE, ALBIGLUTIDE, SEMAGLUTIDE, AND DULAGLUTIDE)

Incretin mimetics belong to a class of drugs that help improve how much insulin the body can make. Incretins are natural hormones that come from the gut and include glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors.

GLP-1 agonists are given by injection and are prescribed for people with type 2 diabetes who have not been able to control their glucose with metformin. They can be taken in combination with other drugs or alone. Recent studies have shown beneficial effects of these medications to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease

Exenatide (Byetta) was the first GLP-1 agonist drug. Exenatide is injected twice a day, 1 hour before morning and evening meals. Bydureon is an extended-release version of Byetta that requires injection only once a week.

Liraglutide (Victoza) is another GLP-1 agonist that is injected once a day. Albiglutide (Tanzeum) is another GLP-1 agonist.

Dulaglutide (Trulicity) and semaglutide (Ozempic) are long-acting drugs in this class of medicines that need to be given only every week. It can be given with several of the other oral agents.

The first of these medications available as an oral medication is also now available (semaglutide).

Side Effects

These drugs stimulate insulin secretion only when blood sugar levels are high and so have less risk for causing low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) when they are taken alone. However, the risk for hypoglycemia increases when GLP-1 inhibitors are taken along with a sulfonylurea drug or insulin. There does not appear to be a risk for hypoglycemia when they are used along with metformin.

Other side effects may include nausea, which usually disappears after about a week. Exenatide may cause new or worse problems with kidney function, including kidney failure. People with severe kidney problems should not use this drug.

There have been safety concerns that incretin mimetics may be associated with pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas) and pancreatic cancer. In 2014, the US FDA and the European Medicines Agency released a joint assessment that these drugs do not appear to cause pancreatic conditions. Regardless, these drugs are often not used for those with a history of pancreatitis.

DPP-4 INHIBITORS (GLIPTINS)

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, also called gliptins, are the second class of drugs that work through the incretin pathway. Drugs available in the United States from this class include sitagliptin (Januvia), saxagliptin (Onglyza), linagliptin (Tradjenta), and alogliptin (Nesina).